Beginner

This beginner course provides the foundation we build on in the basic and advanced options courses. In this course you will learn all the fundamentals of stocks. This is important, because understanding options requires first understanding what these are.

At the end of this course you should:

- have an understanding of what stock is

- know how a stock trade is executed

- understand critical terminology used on this site and in other investment media

What Stock Is

|

When people start a business by incorporating, that is, forming a corporation, they have to specify how many shares of company the stock begins with. They issue these to the owners, called shareholders. This is true of both publicly traded companies and completely private companies. When a company decides to list its shares in public stock markets (also known as "going public") it chooses an exchange, like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or Nasdaq. It finds banks to underwite the public offering. They help the company decide how many and what kind of shares to offer and prepare the prospectus, a document investors use to determine whether to buy in the intial offering. On the first day of the offering the company issues the shares to be traded on the exchange it chose, and the exchange is where it will be traded from then on. |

|

Stock is how a company divides its total value up, into units called shares.

We buy and sell these shares of a company’s stock on the public markets. Sometimes (often, actually) we shorten this and say we’re buying or selling shares of a company. The stock that is available to trade in a market is often referred to by its ticker symbol, e.g., “AAPL” for “Apple”. The same ticker symbol is used in options listings.

These all mean the same thing:

- “I bought 10 shares of Apple”

- “I bought 10 shares of Apple stock”

- “I bought 10 shares of AAPL”

Long and Short

When you buy shares, you are long the stock. For example, if you buy 5 shares of TSLA (Tesla), you are “long Tesla”. This simply means you have bought the stock, presumably with an expectation that it will rise in value so you can later sell it for a profit.

Some brokers permit selling stock that you don’t actually own. They will find someone to lend you shares which you can sell. Doing this makes you short the stock. For example, if you borrow 5 shares of F (Ford) and sell them, you are “short Ford”. This is called a short sale.

A Word on Terminology

“The market” refers to a broad group of organizations and individuals that make and facilitate the trading of securities.

A security is anything that represents something of monetary value, but isn’t itself directly equivalent to cash.

Examples:

- shares of a company stock

- an option contract

- a municipal bond

Some securities, like stock or government treasuries, are created and issued (sold, released for public trading) directly by an entity such as a company or government. Other securities derive their value from these more fundamental securities, for example, options contracts. These are called derivatives.

A deriviative or derivative security is a security that depends on the existence of another security, called the undelrying or underlying asset. Some or all of the value of a derivative is determined by the value of the underlying.

Examples:

- option contracts

- futures contracts

Stock Trading Mechanics

|

There is a lot of "machinery" behind the scenes to make the markets efficient at trading securities. A high-level summary of the process is:

|

There is a lot to unpack in this overview, so we’ll go through step by step.

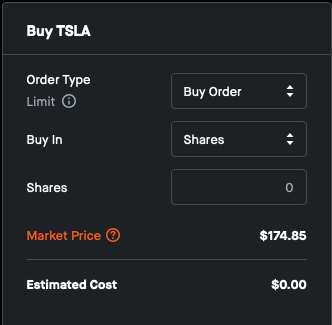

Placing an Order

When someone decides to buy or sell stock, they place an order with their broker. The order has several components.

A Stock Order has several components:

- The type of the trade: buy or sell

- The price–the amount of cash the person is willing to pay to buy (or receive when selling)

- The order type, which is either a market order, a limit order, or a “stop” order (see below)

- The duration the order is good for, usually “Good For Day” (until the end of the trading session) or “Good Until Cancelled” (good until the buyer cancels the order, or some long period of time, e.g., 90 days, set by the broker passes)

|

|

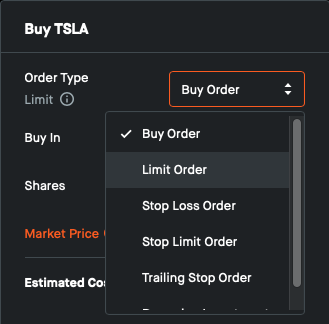

Market Orders

A market order is an order to buy or sell at whatever the market price is. The “market price” is the price that the market maker has when it matches a buyer with a seller. It is not necessarily the buyer or seller sees in their broker’s trading system.

Limit Orders

A limit order is an order where the buyer or seller sets a fixed price (per share). The trade will occur only if the market maker is able to find a match at the specified limit price.

“Stop” Orders

These order types are used to assist in automating management of your portfolio value. This topic is discussed in more depth in the trading material.

- Stop Loss orders are limit orders you place that instruct your broker to sell the stock if it drops below a certain fixed value or by a certain percent. In this way, you minimize the losses when a stock you buy drops rapidly.

- Stop Limit orders are limit orders placed to instruct your broker to sell the stock if it rises by a certain value or percentage. This is also done for cash management, usually to ensure you get some minimum desired profit when the stock price goes up, and before it comes back down.

- Trailing Stop orders are a bit more complicated. These are set like stop loss orders, however the stop price goes up if the stock price goes up. Importantly, it does not go down if the stock price goes down.

Suppose you want to buy a stock for $25. You want to sell if the price drops to $23 or below in order to minimize your losses, in case the company starts performing poorly. But you also will accept a small profit if it moves up. You decide to place a “trailing stop” order with the initial stop at $2.

Suppose the stock’s price increases to $30 and then falls to $27.

- The stock’s price went to $30, and since the trailing stop “follows” the upward movement, at the instant the stock hits $30, the trailing stop price will be $28.

- Because the stock then went down to $27, your stop order would have been filled: you’d collect $28

Exercises

- You buy 100 shares of stock for $30 with a stop loss order set at 10%. Will your stock be sold if the stock price drops to $25, and if so how much cash will you receive?

- David buys 1000 shares of AAPL for $140, with a trailing stop of $10. If AAPL’s price increases to $148, what is the new stop loss price? If AAPL instead falls to $137 before its price rises, what is the stop loss price?

Market Makers

When a broker receives an order it will place the order in a “bucket” with other orders, and have market makers bid on handling the orders.

A market maker is central to the efficient flow of trades in a market. They, not the broker, are ultimately responsible for ensuring every buy order is matched to a sell order, and vice versa. Their function costs money–for employees, offices, computers, etc.–so how do they make money? The answer: they set a bid-ask spread for every stock.

When you place an order for trading stock, you’re actually buying from or selling to a market maker. The maker then matches buy orders with sell orders, and sell orders with buy orders.

They pay stock sellers the bid price, and they collect the ask price from buyers. The market maker pockets the difference.

Bid-Ask Spread

Listed prices for stocks are not necessarily the true price one will pay (or receive) for buying (selling) a stock. Instead, there is the concept of a “bid-ask spread”: the difference between the price a market maker is willing to pay (bid) for a stock and the price they’re willing to sell (ask) the stock for.

The bid price is the highest price the market maker is willing to pay for a stock.

The ask price is the lowest price the market maker is willing to receive for a stock.

|

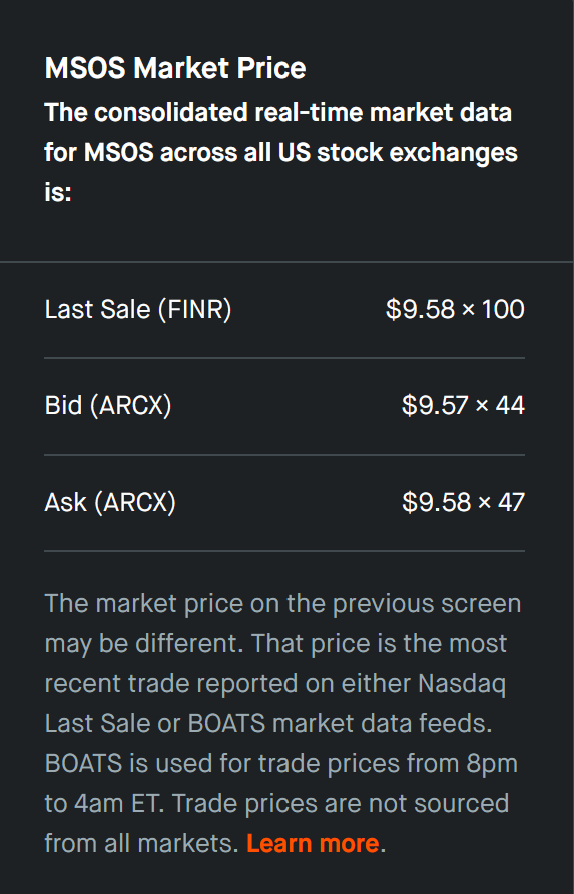

When you're using your broker's trading application, most likely you'll see the ask price when you go to place an order. You'll often see the bid price and the ask price listed along with the stock price in any screen where you're placing an order or viewing more in-depth information about the stock. These bid and ask prices are set by the market makers handling orders. As seen in the example to the left, sometimes the specific exchange used to pool the orders (in this case, ARCX) is also shown. |

Technically speaking, the bid-ask spread fluctuates similarly to the stock prices themselves. So the bid-ask spread you see when placing an order is more like a snapshot in time. When the market maker actually matches orders up, the bid-ask spread for any specific match may differ slightly. These are details managed entirely within the market maker’s systems, and they’re rarely of concern to a retail trader.

Orders and Bid-Ask Spread

When you place an order to buy or sell a stock, market makers will try to match based on the bid-ask spread.

For example, if you place a buy order with a limit price of $100, market makers will try to find someone willing to sell at a lower price to match the order, so they can profit off the bid-ask spread.

When the market maker finds a match for a given order, the trade is executed: cash trades hands, and so do shares of the stock.

Exercises

- A stock is listed at $100 and the bid-ask spread is $0.25. John wants to sell shares at $100 each. What price is the market maker looking for a buyer at?

- A stock has a bid price of $50 and an ask price of $51. What is the bid-ask spread?

Settlement

When the market maker executes the trade, it enters the settlement period.

- Money trades hands: from the buyer to the market maker, and from the market maker to the seller. This happens transparently; buyers and sellers don’t actually interact with the market maker directly.

- Shares are taken from the seller and given to the buyer. The buyer becomes a shareholder of record when the shares are delivered.

The trade is not considered final until the buyer receives the shares and the seller receives cash, both of which may take some time.

Historically these exchanges would mean delivering actual paper stock certificates, or some other similar note indicating ownership, to the buyer and cash to the seller. That took time, and so there was always a settlement period. In modern times cash is transferred instantly. The use paper certificates of stock (or other securities) is a rarity–most records are kept electronically. For a long period of time the settlement period for stocks was 5 days. In 1993 the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) reduced it to 3 days, and today it is 2 days.

The settlement period is sometimes denoted with a capital T and a number indicating the number of business days to settlement of a trade. For example, “T+2” indicates that the settlment date is 2 days after the date of the trade.

The trade is considered final after the settlement period. The date this occurs is the settlement date.

For stocks, currently the settlement date is always 2 business days after the trade. Even though cash is transferred instantly, it is not considered “settled” until the settlement date.

Examples:

- If you buy a stock on Monday, the settlement date is Wednesday.

- If you buy a stock on Thursday, the settlement date is the next Monday.

The SEC sets rules, and some brokers have their own additional rules, for trading with cash received before the settlement period ends (known as “unsettled cash”). Your broker may not even allow you to trade (i.e. buy) with cash that isn’t settled.

Exercises

- Kevin buys 30 shares of TSLA (Tesla) for $175 each. and Robert is on the selling side of the trade. Kevin makes his purchase on Tuesday. On what day will Robert receive his cash? On what day is the trade considered settled?

- There is a market for bonds which have a T+4 settlement period. If Alicia buys a bond on Wednesday, on what day will she be the owner of record of the bond?